U.S. Route 17, or Kings Highway, a path forged by pioneers that linked Boston to Charleston, S.C., is a pathway that has stood the test of time. For centuries, it has connected people from different regions, and today it’s a bustling thoroughfare replete with hotels, restaurants, and shops. But once upon a time, it was a route of danger, a treacherous and challenging journey that snaked through the inhospitable Grand Strand region. A good 300 years ago, Kings Highway was a harsh and arduous stretch of road to traverse. Horse-drawn carriages and riders had to contend with obstacles such as sandy dunes, scrub brush, and swamps, which probably made them want to head home. Those who dared to settle in this uninviting land were a hardy bunch; many of their descendants remain in the area today.

U.S. Route 17, or Kings Highway, a path forged by pioneers that linked Boston to Charleston, S.C., is a pathway that has stood the test of time. For centuries, it has connected people from different regions, and today it’s a bustling thoroughfare replete with hotels, restaurants, and shops. But once upon a time, it was a route of danger, a treacherous and challenging journey that snaked through the inhospitable Grand Strand region. A good 300 years ago, Kings Highway was a harsh and arduous stretch of road to traverse. Horse-drawn carriages and riders had to contend with obstacles such as sandy dunes, scrub brush, and swamps, which probably made them want to head home. Those who dared to settle in this uninviting land were a hardy bunch; many of their descendants remain in the area today.

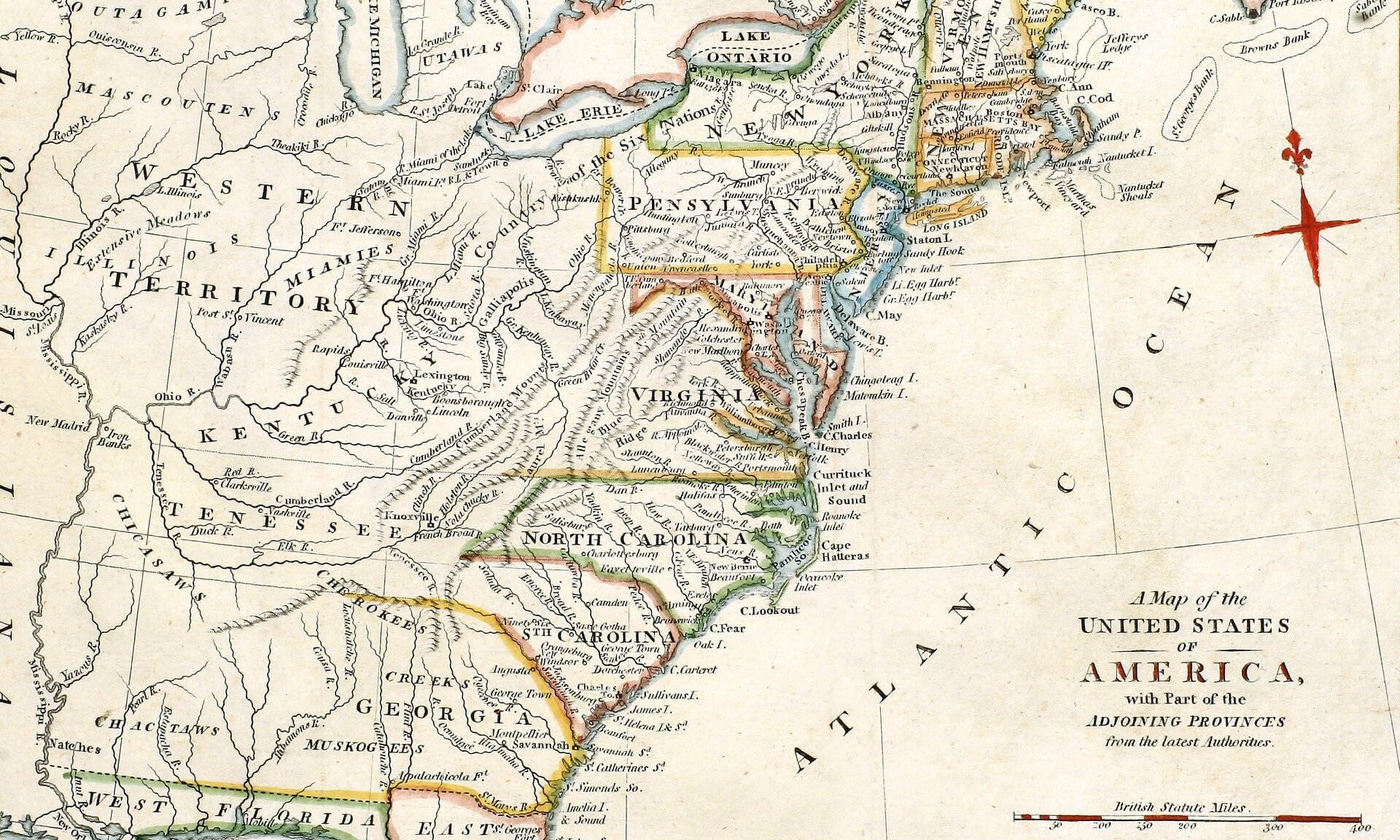

The earliest settlers of the Carolinas are recorded on a mammoth map titled “An Accurate Map of North and South Carolina with Their Indian Frontiers.” Created in 1779 by cartographer Henry Mouzon, this map shows the names of early settlers like Vereen, Lewis, and Bellamy alongside geographical features like creeks, marshes, and swashes. The Grand Strand region reveals the true grit of those who put down their stakes, and we can’t help but wonder if they had a tough time pronouncing the word “swashes.”

Back then, the region was known as Long Bay with few inhabitants in South Carolina. The present-day Highway 17 was an unpaved, sandy, and often indefinable course. While most travelers of the day found it easier to make the journey by sea, trips by land were sometimes necessary. Following what had largely been a path laid out by Native Americans, the route was completed by 1735, with stagecoaches making the 1,300-mile trek by 1750.

The year was 1791, and President George Washington embarked on a journey through the Southern states intending to unite the new country. He left Philadelphia on March 21, with a grand entourage, including Major William Jackson, his valet de chambre, two footmen, a coachman, and a postilion. His carriage was a white chariot drawn by four horses, with four additional saddle horses accompanying the procession.

Washington entered South Carolina, just north of Little River, where he dined with James G. Cochran, a Revolutionary War veteran, at Cochran’s Bay, located behind the Food Lion store in Little River. As he traveled along King’s Highway (a stretch of beach), the President’s hat blew off so frequently that the place was named Windy Hill, a community now part of North Myrtle Beach.

Just south of North Myrtle Beach, he lodged for the night with Jeremiah Vereen, about two miles north of Singleton’s Swash. Vereen guided the President across the swash the next day, and they traveled down the strand for 16 miles, where they turned inland and went five more miles to the home of George Pawley, located in the area of present-day Surfside Beach. There, the President had dinner and fed his horses.

In his diary, President Washington noted that the journey was not without its difficulties. At times, the swash was impassable, and the shifting sands made it treacherous. Nevertheless, he traveled with ease and celerity and was met with kindness along the way. After lodging at Dr. Flagg’s house, which was about 10 miles from Pawley’s and 33 miles from Vereen’s, the President continued his journey, leaving his mark on the Grand Strand.

Despite the difficulties, a few brave souls saw potential in the rugged frontier and carved out their futures in the district. With lots of land available and few takers, most found themselves in possession of large properties that were later subdivided among their children. We can imagine that they probably bragged about how they made it through Long Bay.

Fast forward to 1940, Kings Highway was paved, and the Grand Strand was transformed from a barren territory to one of the nation’s top tourist destinations. The area had undergone a facelift and was now where people flocked instead of fleeing. The Grand Strand had changed so much that if the early settlers saw it today, they’d wonder if they were on the right planet. It’s a wonder what some asphalt and a few decades can do.